By popular demand, I have resurrected this phylogeny from my old website for Easter 2013. I have added a number of extra groups, updated the angiosperms according to APG-III, and repositioned the Gnetales according the apparently ascendent gnetifer hypothesis. The rotated titles in the table appear to work in IE9, Chrome and Safari, but YMMV.

| Classification | Image | Description | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Streptophytes |

Charophytes (stoneworts) |

|

Stoneworts (this is Chara globularis), are the closest relatives to the land plants amongst the green algae. They differ from most other green algae in growing from a well-defined meristem: the ‘bud’ at the top of a land plant’s stem. [CC-BY-SA-3.0 Christian Fischer] |

|||||||||||||

|

Embryophytes |

Marchantiophytes (liverworts) |

Marchantiopsids |

|

Thalloid liverworts like Marchantia polymorpha grow as a flattened, branching leaf-like thallus, held to the ground by rhizoids, which are similar to the root hairs of larger plants. The reproductive structures (the ‘umbrellas’ in this image) are the result of fertilisation of the liverwort by sperm from another of the same species. [CC-BY-SA-3.0 Manfred Morgner] |

||||||||||||

|

Jungermanniopsids |

|

Leafy liverworts like Scapenia asperalook rather more like mosses. Like other liverworts, they have no cuticle, the waxy coat on plant leaves that stop them drying out. Consequently liverworts often live in damp places, such as greenhouses, forest floors and near streams. [Copyright-free, image credit Hermann Schachner]. |

||||||||||||||

|

Bryophytes sensu stricto (mosses) |

Bryopsids |

Core bryopsids |

|

The majority of mosses (over 10 000 species) fall in the bryopsid group. They are small, easily overlooked, but absolutely ubiquitous. This is Bryum capillare, growing on a tombstone. [CC-BY-2.0 ndrwfgg@Flickr] |

||||||||||||

|

Polytrichopsids |

|

Some of the polytrichoid mosses, like this Dawsonia superba have water-conducting tissues similar to those in vascular plants, which allow them to grow much taller than most other mosses. [CC-BY-SA-2.5 Velela] |

||||||||||||||

|

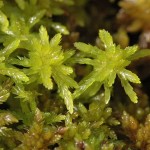

Sphagnopsids |

|

Sphagnum flexuosum and related species of moss are the dominant species of vast tracts of mire and bog, and their dead bodies are a major contributor to the peat that you really shouldn’t be using to pot your houseplants. [CC-BY-SA-2.5 James Lindsey at Ecology of Commanster] |

||||||||||||||

|

Anthocerophytes (hornworts) |

|

The gorns of hornworts, like this Anthoceros agrestis are the diploid reproductive structures. In mosses and liverworts, most of plant you see is haploid (only has one set of chromosomes): the diploid stage (two sets like humans and most other plants) is generally small; in hornworts it is rather larger. [CC-BY-SA-3.0 BerndH] |

||||||||||||||

|

Tracheophytes |

Lycophytes |

Clubmosses sensu stricto |

|

The true clubmosses, like this Lycopodium pinifolia look something like a stretched pinecone. Clubmosses are not mosses at all: they are actually more closely related to daisies than they are to mosses, as the cladogram on the left shows. They are fully vascular and reproduce by spores, like ferns. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||

|

Spikemosses |

Spikemoss |

|

Spikemosses, like this Selaginella martensii watsoniana, show a beautiful fractal structure. The resurrection plant (S. lepidophyllus, withstands drying that would kill most other plants. Extinct relatives of spikemosses and clubmosses include Zosterophyllum and Sawdonia, which like these plants, lack true leaves. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Quillworts |

|

The squashed trunks of Lepidodendron and Sigillaria are major contributors to coal, formed in coal forests during the Carboniferous period. The last remaining close relatives of these giant clubmosses are quillworts, like Isoetes melanospora. Many are endangered, but not quite as photogenic as a panda. [CC-BY-SA-3.0 ARH12] |

||||||||||||||

|

Euphyllophytes |

Ferns sensu lato |

Whiskferns |

|

Whiskferns have had a chequered classificatory history. For many years, the similarity of whiskferns (this is Psilotum nudum; the other main genus is Tmesepteris spp.) to the first vascular plants (Cooksonia and Rhynia) led botanists to think they were the sister group of the rest of the vascular plants. However, molecular evidence points to their being closely related to ferns. [Copyright-free, image credit Peter Woodard] |

||||||||||||

|

Ophioglossids |

|

The adders-tongue fern Botrychium lunaria and its allies have been traditionally classified with the rest of the ferns, but molecular evidence groups them with the whiskferns. [CC-BY-SA-3.0 Abalg] |

||||||||||||||

|

Equisetophytes (horsetails) |

|

The horsetails (this is Equisetum telmateia) are the tiny remnants of a once hugely important plant group, which included the Carboniferous giant horsetail Calamites. The ferns and other vascular plants differ from the clubmosses in having true leaves, probably formed by webbing across small branches. One of the first plants with this feature was Trimerophyton. [CC-BY-SA-3.0 Steve Cook] |

||||||||||||||

|

Ferns |

Marattids |

|

Marattia is a tropical fern, one of this large group of overlooked plants. Ferns are actually very common, and although often associated with damp places, there are desert species, and one of the most successful plant species on Earth is bracken. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Leptosporangiates |

|

The ferns are the second most diverse of the three groups of vascular plants. The largest group, of some 10 000 species are the leptosporangiate ferns: this one is Asplenium bulbiferum. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||||

|

Spermatophytes |

Angiosperms |

Waterlilies |

|

The waterlilies (this is a giant, Victoria amazonica), are sister group to most of the rest of the flowering plants, although Amborella trichopoda is currently fingered as sister to all of them. Being denigrated as the most ‘primitive’ living angiosperm is an honour previously bestowed upon Magnolia, Ceratophyllum and others. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||

|

Mesangiosperms |

Magnoliids |

|

This is Liriodendron tulipifera, a close relative of the magnolia. The evolution of the angiosperms has always been contentious: the Gondwanan tongue-ferns (Glossopteris), Pentoxylon, Caytonia and Cycadeoidea have all been touted as close relatives, but the jury is very much still out. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Monocotyledons |

Alismatids |

|

The aroids, including Arisaema ringens are members of the huge and important group of monocot plants, which bear seeds with only one seed-leaf. Aroids exploit insects, which is a common strategy amongst the flowering plants. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Core monocots |

Asparagales |

|

It’s difficult to do justice to the diversity of 300 000 species of flowering plants, but you all know what irises, daffodils, orchids (this is a Paphiopedilum cultivar), and agaves look like, so I’m trying to give more space to the things you’ve never heard of instead. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Commelinids |

Palms |

|

The palms (e.g. Johannesteijsmannia magnifica), are an exception to the rule that monocots are herbs not trees. Monocots in general cannot make true wood: the trunk of a palm-tree cannot get thicker with age, like those of dicot trees like oaks. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Grasses |

|

Zea mays, an economically important grass (maize), will represent the huge commelinid clade, which includes grasses, sedges, rushes, bromeliads (pineapples), and a vast number of other important monocot plants. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||||

|

Eudicots |

Ranunculids |

|

The ranunculids branch deeply from the other major lineages of dicots. This is Papaver orientale, the oriental poppy; other ranuculids include the buttercups. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Core eudicots |

Caryophyllids |

|

The caryophyllids include many of the carnivorous plants, like this Nepenthes cultivar, and all the cactuses. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Asterids |

Campanulids |

|

The campanulids are a sub-clade of the asterids, containing bellflowers, ivy, composites like daisies, and umbellifers like carrots. Many of these species have reduced flowers clumped into larger inflorescences: thistle ‘flowers’ (this is Silybum marianumare actually hundreds of tiny flowers squished into a spikey cup. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Lamiids |

|

The lamiids are the other main group of asterids, including the economically important mint and potato families. This is Digitalis purpurea, the foxglove, source of the drug digoxin. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||||

|

Rosids |

Fabids |

|

Ulex europaeus, the gorse, is a member of the fabid sub-clade of the rosids. The fabids include many familiar flowering plants, such as roses, beans, apples and oaks. The rosids and asterids are the main groups of dicot plants, which are those with two seed leaves. Many of the fabids are symbiotic with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Malvids |

|

The second main group of rosids are the malvids, which include mallows, cabbages, Citrus fruits, and mango. I was going to illustrate this with dear old Arabidopsis, but the botantists’ fruit-fly is a little dreary-looking. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||||

|

Gymnosperms |

Cycads |

Cycadaceae |

|

Cycads like Cycas revoluta and the other 1 000 species of gymnosperms (plants with ‘naked’ seeds not enclosed in fruits) seem to be the sister group of an extinct lineage of ‘progymnosperms’, which includes Archaeopteris (one of the first trees) and other ‘seed-ferns’. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||

|

Zamiaceae |

|

The other main lineage of cycads (the Zamiaceae) includes Encephalartos ferox. Like other cycads, the plants are either male or female, and look much like palms, to which they are not at all closely related. [CC-BY-SA-3.0 Steve Cook] |

||||||||||||||

|

Ginkgo |

|

Ginkgos are the last remaining species of maidenhair tree, a once common group. Ginkgo biloba is now only found in captivity. This one is called Fanny and lives in my parent’s garden. [CC-BY-SA-3.0 Steve Cook] |

||||||||||||||

|

Gnetifers |

Conifers |

Pines |

|

Pinus and its relatives are conifers, characterised by their cones and needle-like leaves. Many of these species are found in the northern (Laurasian) hemisphere, named after the northern continent of the Carboniferous period. The flora of Laurasia is quite distinct from… [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||

|

Monkey puzzles |

|

…the flora of the southern (Gondwanan) hemisphere, including the monkey puzzle Araucaria araucaroides. The Gondwanan fauna is also quite distinct: marsupials are also found mostly in South America and Australasia. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||||

|

Cupressids |

Yews |

|

The yews (Taxus baccata), are often found in churchyards in England. However, the trees are actually older than the churches in many cases, and are probably associated with pre-Christian sites of pagan worship. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Cypresses |

|

The cypresses include Sequoia sempervirens, the tallest plant on earth, and the Cupressus × leylandii, the scourge of suburban gardens. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||||

|

Gnetophytes |

Welwitschia |

|

Welwitschia mirabilis is one of the gnetophytes, a group whose placement has been contentious for decades. Morphological and molecular data conflict wildly, the currently favoured position is sister to the conifers. Welwitschia only ever grows two huge ribbon like leaves, and has cone-like flowers. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

|||||||||||||

|

Gnetum |

|

Gnetum gnemon is a member of the type genus of this group, the gnetophytes. Welwitschia is a desert shrub, whereas Gnetum are tropical trees and vines. All gnetophytes have an unusual double-fertilisation that is only otherwise found in angiosperms. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||||

|

Ephedra |

|

Ephedra sinica is a final member of this group. The drug ephedrine, which is used as a nasal decongestant, is extracted from this grass-like herb. [CC-BY-2.0 Alex Lomas] |

||||||||||||||